The Definition of Investment Consulting including Typology and Segmentation

According to Steele ‘consulting’ is ”any form of providing help on the

content, process, or structure of a task or series of tasks, where the

consultant is not actually responsible for doing the task itself but is

helping those who are.”[1]

A commission of experts in the USA has defined ‘management consulting’ as ”an independent

and objective advisory service provided by qualified persons to clients in

order to help them identify and analyze management problems or opportunities.

Management consultants also recommend solutions or suggested actions with

respect to these issues and help, when requested, in their implementation.”[2]

Kubr combines – in collaboration with an international circle of authors – the contents of these

two definitions and concludes: ”Management consulting is an independent

professional advisory service assisting managers and organizations to achieve

organizational purposes and objectives by solving management and business

problems, identifying and seizing new opportunities, enhancing learning and

implementing changes.”[3]

The term ‘management consultant’ can be defined as “a universal term for any

professional who provides assistance to others, usually for a fee.”[4]

All four definitions include the essence on which consulting is based: independent

assistance with problem solving.[5]

The existence of a problem is, thus, constitutive for a consulting demand.[6]

Unlike the

expert who solves a problem on his own, the work of a consultant is

characterized by interaction with the client in solving the problem.[7]

This interaction is reflected, on the one hand, in the consultant’s

understanding of the client’s affairs and, on the other hand, in the

collaboration between consultant and client.

Moreover, the criterion of specialization in the expert sense is not sufficient since

independence is another constitutive element of an external consultant:

“Outside advisors brought specialized knowledge, not otherwise available, into

organizations that faced problems that internal staff members could not easily

resolve,” but “it is not their specialization that sets consultants apart but

their continuing independence from the corporation.”[8]

In 1982, Turner presented a hierarchy of eight levels that illustrate the

consulting tasks in a differentiated manner thereby contributing to an even

more detailed definition:[9]

- Information conveyance

- Diagnosis of current state to redefine the problem

- Problem resolution

- Recommendations for action based on the diagnosis

- Implementation support

- Development of a joint understanding and commitment

- Support for organizational learning

- Permanent improvement of organizational effectiveness

According

to Fink, management consultants ‘make’ management concepts. They invent the

basic principles, design methods and instruments, and, that way, solve the

problems of their clients.[10]

Insofar, also knowledge transfer is, besides problem solving, a dominant

function of consulting[11];

thus, knowledge is a central parameter in the definition of consulting.[12]

Besides

law firms, auditing companies, and also investment banks, investment

consultants are among ‘professional service firms’ that perform particularly

knowledge-driven services.[13]

Other functions that can be classified as latent are:

- Political function, i.e., use of a consultant to assert unshakeable notions and already

a-priori made decisions.[14]

- Enforcement function, i.e., use of a consultant to support the achievement of a consensus in case of still variable notions and open decisions.

- Legitimation function, i.e., use of a consultant to block or at least reduce attribution of unfavorable or unpleasant developments to the management in charge.[15]

- Interpretation function, i.e., use of a consultant as (external) conversation and sparring partner to obtain new insights and perspectives through contemplation.

Regarding the

political function of consultants, McKenna states that “administrators have

employed outside advisors for thousands of years, but their counsel has

traditionally been political, not commercial.“[16]

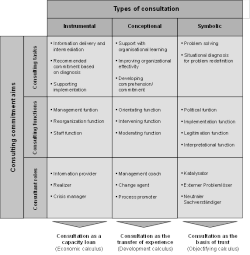

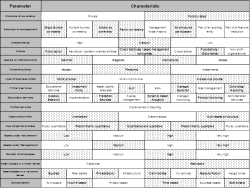

For a deeper understanding of consulting in general, it is advisable to take a look

at the roles.[17]

Since it is not expedient or even possible in the framework of this study to enumerate all the possible roles of consultants as “the list of roles is

endless,”[18]

the following figure offers an integrative observation of roles, functions, and

tasks of consultants.[19]

Fig. 1: Tasks, functions, and roles of consultants.

[20]

The term ‘investment consultant’ is not a protected professional title. This is also the

reason for the lack of any official or generally recognized, clear and

unequivocal definition. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

subsumes investment consultants under the term ‘investment advisers:’ “A person

that advises as to the selection or retention of an investment manager is

considered an investment adviser”[21].

Yet, according to Mohe et al. the lack of a profession in the socio-professional

sense […] does not necessarily [mean] the leave-taking from notions of

professionalism as defined in a knowledge-sociological sense.[22]

Literally, the term ‘investment consultant’ refers to a consultant in matters of the asset

side of a balance sheet. Consultants who are solely specialized in the analysis

of the liability side and in actuarial consulting are, strictly speaking,

called ‘pension consultants.’ The meaning, however, covers in fact a much wider

scope than that.

If the term ‘management’ is replaced by ‘investment’, the above-mentioned definitions of

management consulting largely provide a fitting template for a practice-oriented

real definition[23]

of investment consulting:

Investment consulting is

an independent professional consulting service,

which interactively – directly and as an intermediary –

supports institutional investors and their decision-makers

through solving investment problems

to optimally achieve their financial objects and goals

For systematic specification of the roles of investment consultants, the

classification of the roles of management consultants according to Schein will

be applied.[24]

Investment consultants’ activities, as well as value-creation fields

respectively, will be classified along those of management consultants and will

be dealt with extensively and in a detailed manner in the following chapters.

In the framework of the ‘physician-patient relationship’ according to Schein, a

customized solution is recommended following a comprehensive and detailed

analysis of the client’s situation. In investment consulting, the following

value creation steps must be attributed to that class: definition of investment

policy, asset-liability analysis, and strategic asset allocation. With the

‘purchase of expertise’ according to Schein, the client makes use of the

specific knowledge and expertise of the consultant in this area: These include

such services as manager selection, allocation, and monitoring. In ‘process

consulting’ according to Schein, consultants assist with their methodological

competences, among them, services implementation as well as investment

controlling.[25]

The essence of investment consultants’ classic roles – i.e., in the narrow sense[26]

– is that “the role of the investment consultant is to manage, not to make

investment decisions.”[27]

In the same way the general roles of management consultants also apply to

investment consultants, as do, by nature, the general functions. Investment

consultant-specific functions pertaining to investment-related questions are

the quality assurance function and the intermediation function.

Through professional ‘screening’ as well as due diligence in the framework of manager

selection, investment consultants reduce an information asymmetry that

basically exists at all times, thereby contributing to an increase and

respectively assurance of their clients’ quality of decisions. The

intermediation function is the result of investment consultants being

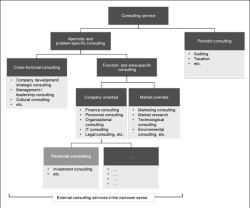

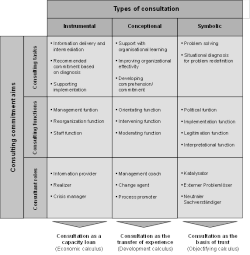

effectively active as ‘mediators.’ The following figure serves the

classification of investment consulting within the context of various

consulting services – and, thus, the distinction from other service types:

Fig. 2: Investment consulting within the context of various consulting services.

[28]

This systematic classification and distinction enables an abstraction from the

practice-oriented real definition and, that way, leads to a theory-oriented

real definition of investment consulting:

Investment consulting is

an external,[basically aperiodic,] problem-specific and

function – resp. area-specific consulting service,

which represents a form of financial consulting for institutions.

through solving investment problems

to optimally achieve their financial objects and goals

Typology and Segmentation

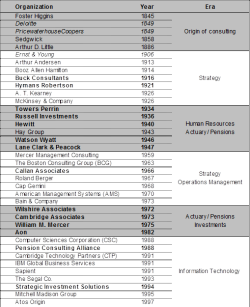

The roots of modern consulting are in the USA[29]

and can be traced back to the first half of the 19th century. Foster

Higgins (1845), Sedwick (1858), and Arthur D. Little (1886) are considered to

be the first consulting companies, whereby especially the latter is seen as the

precursor of management consulting.[30]

In the 1820s, the choice of professional and external management services increased rapidly.

A broad spectrum of options developed through consulting-related professions

such as lawyers, accountants, and bankers. The profile of classic management

consulting such as we know it today emerged only with the establishment of

eventually world-renowned consulting companies such as Arthur Andersen (1913),

Booz Allen Hamilton (1914), and McKinsey & Company (1926). Very beneficial

in this context was the separation of commercial and investment banks through

the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Until then, numerous tasks that nowadays are

part of the core business of management consulting had been performed by

commercial banks.[31]

Besides the prohibition of emission of and trade with shares, this law also

prohibited commercial banks to engage in business consulting and reorganization

on behalf of their corporate customers.[32]

In the second half of the 20th century, further important consulting companies

were founded such as The Boston Consulting Group (1963), Roland Berger (1967)

as well as Bain & Company (1973). Also during that period, many consulting

companies began to accelerate their internationalization and expanded their

activities into Europe. US-American companies have been dominating the

management consulting market worldwide ever since.

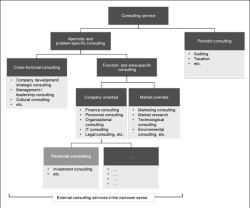

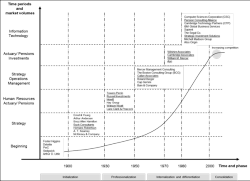

The following figure provides a chronological overview of the establishment of

consulting companies in general and, thus, of the genesis and historical

development of investment consulting:

Fig. 3: Founding years of important consulting companies.

[33]

The above chronology of company foundations includes classic management consultants,

consulting companies focused on auditing (cursive) as well as on pension and

investment consultants (bold).

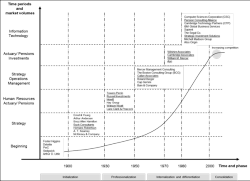

The history of how the consulting market evolved can be divided into three major

periods, which represent the defining stages; these are: initialization,

professionalization, internationalization, and concomitantly differentiation as

well as consolidation. The following figure shows the attribution of investment

consulting to periods and stages of the consulting market:

Fig. 4: Development periods and stages in the consulting market.

[34]

The time before 1930 can be described as initialization since it was only then that

today’s consultant profile evolved. The establishment of Buck Consultants (USA)

and Hymans Robertson (UK), two investment consultants still active to this day,

occurred already at that stage. The subsequent years into the 1960s are

considered to be the professionalization stage since with increasing demand

from industrial companies, methods and concepts kept developing. The term

‘management consultant’ took roots. The establishment of several investment

consultants operating worldwide today falls in this stage: Russell Investments,

Watson Wyatt[35]

as well as Hewitt[36].

The 1970s were both the start of internationalization, which brought about the

tapping of markets in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, and of differentiation,

through which small consulting companies focusing on specific core areas

evolved. In that phase from 1972 until 1982, a number of still operating

US-American pension and investment consultants were founded: Callan Associates,

Wilshire Associates, Cambridge Associates, William M. Mercer[37]

as well as Aon[38].

Therefore, this decade can be described as the ‘cradle of modern investment

consulting.’ Because of the increasing importance of computers, consulting

companies specialized in information technology eventually evolved in the

1990s.

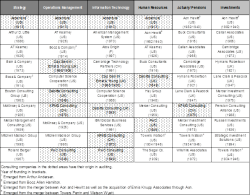

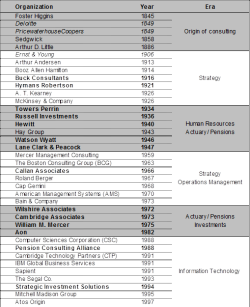

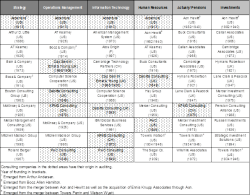

This grouping into periods, i.e., chronological clustering, can be fully converted

into segments of homogenous types of consulting services, i.e., clustering

according to content:

Fig. 5: The ‘Top 10’ consultants worldwide according to segments.

[39]

The origins of the consulting profession are not just in management consulting in general,

but, more specifically, also in strategic consulting (strategy). Later on, the

consulting fields ‘operations management’ and ‘information technology’

developed.

From the above figure it becomes evident that most of the large traditional management

consulting firms focus only on three activities. Thus, a ‘break’ can be

discerned, which divides the segments into two halves[40].

The providers in the segments human resources, actuary/pensions as well as

investments in the second half are to a large extent different firms from those

in the first half.

Furthermore, it becomes apparent that several firms in the second half are among the ‘Top

10’ in several segments. Nevertheless, globally active firms originating mostly

from the USA dominate both the first and second half. Myners states that

investment consultants in the UK have gained market strength to a large extent

based on their actuarial background.[41]

Moreover, it is notable that consulting units that are (PwC and KPMG) or were (Accenture[42])

part of an auditing company are active in the segments of both halves, but not

in the fringe segments.[43]

Nevertheless, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) increased its

pressure on auditing companies to part with their consulting units.[44]

To bypass this requirement, all large firms preventively gave the business

field ‘consulting’ a new designation, ‘advisory’. Also, there are no longer any

‘consultants’, instead there are ‘advisors’.[45]

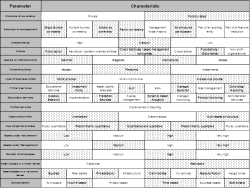

To achieve the typologization and segmentation of an individual investment

consultant, it again makes sense to point out the possibility of a schematical

classification. After all, the scope of individual characteristics is – like in

asset management companies – extremely varied. Individual characterization is

possible based on the morphological box below:

Fig. 6: Typologization criteria of investment consultants.

[46]

References

Binnewies, S. (2002)

(Strategisches Management professioneller Dienstleistungen am Beispiel der Unternehmensberatung):

Strategisches Management professioneller Dienstleistungen am Beispiel der

Unternehmensberatung, Göttingen, Duehrkohp & Radicke.

Biswas, S./ Twitchell, D. (2002) (Management Consulting: A Complete Guide to the Industry): Management Consulting:

A Complete Guide to the Industry, 2nd Edition, New York, New York, John Wiley

& Sons.

Bloomfield, B. P./ Danieli, A. (1995) (The Role of Management Consultants): The Role of Management

Consultants in the Development of Information Tech-nology, Journal of

Management Studies, Vol. 32, Hoboken, New Jersey, Wiley-Blackwell, S. 23-46.

Bower, M. (1982) (The Forces That Launched Management Consulting Are Still at Work): The Forces That

Launched Management Consulting Are Still at Work, Journal of Management

Consulting, Vol. 1, No.1, S. 4-6.

Canbäck, S. (1998) (The Logic of Management Consulting – Part 1): The Logic of Management Consulting –

Part 1, Journal of Management Consulting, Vol. 10, No. 2, Institute of

Management Consultants, New York, New York, S. 3-11.

Caroli, T. S. (2007) (Unternehmensberatung als Sicherstellung von Führungsrationali-tät?):

Unternehmensberatung als Sicherstellung von Führungsrationalität? In: Nissen,

V. (Hrsg.): Consulting Research – Unternehmensberatung aus wissenschaftlicher Perspektive,

Wiesbaden, Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, S. 109-126.

Ernst, B./ Kieser, A. (2002) (In Search of Explanations for the Consulting Explosion): In Search of

Explanations for the Consulting Explosion. In: Sahlin-Andersson, K./ Engwall,

L. (Eds.): The Expansion of Management Knowledge, Stanford, Stanford Business

Book, S. 47-73.

Faust, M. (1998) (Die Selbstverständlichkeit der Unternehmensberatung): Die Selbstverständlichkeit

der Unternehmensberatung. In: Howald, J./ Kopp, R. (Hrsg.): Sozialwissenschaftliche

Organisationsberatung: Auf der Suche nach einem spezifischen

Beratungsverständnis, Berlin, Ed. Sigma, S. 147-181.

Fink, D. (2003) (Managementansätze im Überblick): Managementansätze im Überblick. In: Fink, D.

(Hrsg.): Management Consulting Fieldbook: Die Ansätze der großen

Unternehmensberater, 2., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage, München, Vahlen,

S. 13-24.

Fink, D. (2005) (Machiavelli, McKinsey & Co.): Machiavelli, McKinsey & Co. – eine kleine Geschichte

der Managementberatung. In: Petmecky, A./ Deelmann, T. (Hrsg.): Arbeiten mit

Managementberatern – Bausteine für eine erfolgreiche Zusammenarbeit, Berlin –

Heidelberg – New York, Springer, S. 189-203.

Franck, E./ Pudack, T./ Benz, M.-A. (2003) (Unternehmensberatung als Legitimation): Unternehmensberatung als

Legitimation, Working Paper No. 21, Working Paper Series ISSN 1660-1157,

Zürich, Universität Zürich.

Gattiker, U. E./ Larwood, L. (1985) (Why Do Clients Employ Management Consultants?): Why Do Clients

Employ Management Consultants?, Human Science Press, S. 120-129.

Gummesson, E. (2000) (Qualitative Methods in Management Research): Qualitative Methods in Management

Research, 2nd Edition, Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications.

Heuermann, R./ Herrmann, F. (2003) (Hrsg.) (Unternehmensberatung): Unternehmensberatung – Anatomie und

Perspektiven einer Dienstleistungselite, München, Vahlen.

Kennedy Consulting Research & Advisory (2010) (Consulting Capability Assessments): Consulting

Capability Assessments, http://www.kennedyinfo.com/ consulting/analystservices

/assessments?C=vcRUNkJ5kxwYW0bk&G=qzITtFX263wsHqwC, Peterborough, New

Hampshire.

Kieser, A. (1998) (Unternehmensberater): Unternehmensberater – Händler in Problemen, Praktiken

und Sinn. In: Glaser, H./ Schröder, E./ v. Werder, A. (Hrsg.): Organisation im

Wandel der Märkte, Wiesbaden, Gabler, S. 192-225.

Kleeberg, J. M./ Schlenger, C. (2000) (Die Rolle von Consultants im Rahmen der Spezialfondsanlage): Die Rolle

von Consultants im Rahmen der Spezialfondsanlage. In: Kleeberg, J. M./

Schlenger, C. (Hrsg.): Handbuch Spezialfonds: Ein praktischer Leitfaden für

institutionelle Anleger und Asset Management Gesellschaften, Bad Soden/Ts.,

Uhlenbruch, S. 871-897.

Kraus, S./ Mohe, M. (2007) (Zur Divergenz ideal- und realtypischer Beratungsprozesse): Zur Divergenz ideal- und

realtypischer Beratungsprozesse. In: Nissen, V. (Hrsg.): Consulting Research –

Unternehmensberatung aus wissenschaftlicher Perspektive, Wiesbaden, Deutscher

Universitäts-Verlag, S. 263-279.

Kromrey, H. (2009) (Empirische Sozialforschung): Empirische Sozialforschung, 12., neu bearb.Auflage,

Stuttgart, UTB.

Kubr, M. (Ed.) (2002) (Management Consulting: A Guide to the Profession): Management Consulting: A

Guide to the Profession, 4th Edition, Geneva, International Labour Office.

Maister, D. (2010) (Professionalism in Consulting): Professionalism in Consulting. In: Greiner,

L./ Poulfelt, F. (Eds.): Management Consulting Today and Tomorrow: Perspectives

and Advice from 27 Leading World Experts, New York – London, Routledge.

McKenna, C. D. (1995) (The Origins of Modern Management Consulting): The Origins of Modern Management

Consulting, Business and Economic History, Vol. 24, No. 1, S. 51-58.

McKenna, C. D. (2006) (The World’s Newest Profession): The World’s Newest Profession: Management Consulting

in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global

Enterprise), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Mohe, M./ Heinecke, H. J./ Pfriem, R. (2002) (Beratung als Geschäft): Beratung als Geschäft. In: Mohe, M./

Heinecke, H. J./ Pfriem, R. (Hrsg.): Consulting – Problemlösung als

Geschäftsmodell – Theorie, Praxis, Markt, Stuttgart, Klett Cotta, S. 221-224.

Myners, P. (2001) (Institutional Investment in the United Kingdom: A Review): Institutional

Investment in the United Kingdom: A Review, London, HM Treasury.

Nees, D. B./ Greiner, L. E. (1985) (Seeing Behind the Look-Alike Management Consultants): Seeing Behind the

Look-Alike Management Consultants, Organisational Dynamics, Vol. 13, Elsevier,

S. 68-79.

Niedereichholz, C./ Niedereichholz, J. (2006) (Consulting Insight): Consulting Insight, München – Wien, Oldenbourg.

Niewiem, S./ Richter, A. (2007) (Make-or-buy Entscheidungen für Beratungsdienstleistungen): Make-or-buy

Entscheidungen für Beratungsdienstleistungen – Eine empirische Untersuchung.

In: Nissen, V. (Hrsg.): Consulting Research – Unternehmensberatung aus

wissenschaftlicher Perspektive, Wiesbaden, Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, S.

57-72.

Pensions & Investments (2010) (Research Center): Research Center, http:// www.pionline.com, Crain

Communications Inc., Detroit, Michigan, [accessed on November 12, 2010].

Poulfelt, F./ Greiner, L./ Bhambri, A. (2010) (The Changing Global Consulting Industry): The Changing

Global Consulting Industry. In: Greiner, L./ Poulfelt, F. (Eds.): Management

Consulting Today and Tomorrow: Perspectives and Advice from 27 Leading World

Experts, New York – London, Routledge, S. 5-32.

Schein, E. H. (1988) (Process Consultation Vol. 1): Process Consultation Vol. 1: Its Role in

Organisation Development, 2. Auflage, Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley.

Steele, F. (1981) (Consulting for Organizational Change): Consulting for Organizational Change,

Amherst, Massachusetts, University of Massachusetts Press.

Sturdy, A. (1997) (The Dialectics of Consultancy): The Dialectics of Consultancy, Critical

Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 8, S. 511-535.

Thomson Nelson (2010) (Database): Database, http://www.nelsoninformation. com, Thomson Reuters, New

York, New York.

Trone, D./ Allbright, W./ Taylor, S. (1996) (The Management of Investment Decisions): The Management of

Investment Decisions, New York, New York, McGraw-Hill.

Turner, A. N. (1982) (Consulting Is More Than Giving Advice): Consulting Is More Than Giving Advice,

Harvard Business Review, Vol. 60, September-October, Boston, Massachusetts,

Harvard Business Publishing, S. 120-129.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (2004) (Investment Advisers Act of 1940): Investment

Advisers Act of 1940, Revised through September 2004, Washington, D.C.

Wilkinson, J. W. (1995) (What

is Management Consulting?): What is Management Consulting? In: Barcus, S. W./

Wilkinson, J. W. (Eds.): Handbook of Management Consulting Services, New York,

New York, McGraw-Hill, S. 1-3 bis 1-16.

Ziegler, A. (1995) (Beratung

beim Wort genommen): Beratung beim Wort genommen. In: Wohlgemuth, A. C./

Treichler, C. (Hrsg.): Unternehmensberatung und Management: Die Partnerschaft

zum Erfolg, Zürich, Versus, S. 55-65.

Footnotes

Steele (1981): Consulting for Organizational Change, pp. 2 f.

Wilkinson (1995): What is Management Consulting?, pp. 1-4.

Kubr (Ed.) (2002): Management Consulting: A Guide to the Profession, p. 10.

Biswas/ Twitchell (2002): Management Consulting: A Complete Guide to the

Industry, p. 6.

See Kubr (Ed.) (2002): Management Consulting: A Guide to the Profession, pp. 3 and

7. For an historical and language cultural derivation of the word ‘consultant’,

that also comes to the same conclusion see Ziegler (1995): Beratung beim Wort genommen, pp. 55

ff.

See Mohe/ Heinecke/ Pfriem (2002): Beratung als Problemlösung, p. 131.

See Maister (2010): Professionalism in Consulting, p. 36.

McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, p. 12.

See Turner (1982): Consulting Is More Than Giving Advice, pp. 121 ff.; Gummesson

(2000): Qualitative Methods in Management Research, p. 7.

See Kraus/ Mohe (2007): Zur Divergenz ideal- und realtypischer Beratungsprozesse,

p. 268.

See McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, pp. 8 ff.; Binnewies (2002):

Strategisches Management professioneller Dienstleistungen am Beispiel der

Unternehmensberatung, pp. 38 ff.

See Niewiem/ Richter (2007): Make-or-buy Entscheidungen für

Beratungsdienstleistungen, p. 67.

In the framework of the principal agent theory, the legitimation function of

consultants is assigned great significance, which, however, they are only

partially able to fulfill; see Franck/ Pudack/ Benz (2003): Unternehmensberatung

als Legitimation, p. 10. For a wider-reaching examination on consultants’ legitimacy

see Ernst/ Kieser (2002): In Search of Explanations for the Consulting

Explosion; Faust (1998): Die Selbstverständlichkeit der Unternehmensberatung;

Kieser (1998): Unternehmensberater; Sturdy (1997): The Dialectics of

Consultancy; Gattiker/ Larwood (1985): Why Do Clients Employ Management Consultants?.

McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, p. 10.

For a more thorough inspection on consultants’ roles generally see Bloomfield/

Danieli (1995): The Role of Management Consultants; Canbäck (1998): The Logic

of Management Consulting – Part 1; Ernst/ Kieser (2002): In Search of

Explanations for the Consulting Explosion; Gattiker/ Larwood (1985): Why Do

Clients Employ Management Consultants?; Gummesson (2000): Qualitative Methods

in Management Research, p. 39; Heuermann/ Herrmann (2003): Unternehmensberatung,

pp. 339 ff.; Kieser (1998): Unternehmensberater; Nees/ Greiner (1985): Seeing

Behind the Look-Alike Management Consultants; Sturdy (1997): The Dialectics of

Consultancy. For an earlier and more practice oriented description see Bower

(1982): The Forces That Launched Management Consulting Are Still at Work, pp.

4. ff.

Biswas/ Twitchell (2002): Management Consulting: A Complete Guide to the

Industry, p. 7.

For a consideration of the personal characteristics required from a management consultant

comp. Gummesson (2000): Qualitative Methods in Management Research, pp. 196 f.;

on the necessary competencies see Maister (2010): Professionalism in

Consulting, pp. 38 f.

Illustration on the basis of Caroli (2007): Unternehmensberatung als Sicherstellung

von Führungsrationalität?, p. 117.

Mohe/Heinecke/ Pfriem (2002): Beratung als Geschäft, p. 221.

A real definition is a statement about the essence and the characteristics of a

subject area or a situation that – in contrast to a nominal definition –

implies reality; see Kromrey (2009): Empirische Sozialforschung, p. 155.

See Schein (1988): Process Consultation Vol. 1, pp. 1 ff.

For further specification of the roles see Kleeberg/ Schlenger (2000): Die Rolle

von Consultants im Rahmen der Spezialfondsanlage, pp. 871 ff.

‘Implemented consulting’ and ‘fiduciary management’ are not among the roles in

the narrow sense..

Trone/ Allbright/ Taylor (1996): The Management of Investment Decisions, p.

243.

Illustration on the basis of Caroli (2007): Unternehmensberatung als Sicherstellung

von Führungsrationalität? p. 111.

Especially in Chicago and New York numerous important consulting companies were

founded and are still headquartered there.

For a historical perspective on this subject going back to the origins of consulting

see Poulfelt/ Greiner/ Bhambri (2010): The Changing Global Consulting Industry,

pp. 8 ff.; McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, pp. 145 ff.; Kubr

(Ed.) (2002): Management Consulting: A Guide to the Profession, pp. 31 ff.;

Wilkinson (1995): What is Management Consulting?, pp. 1-9 ff.; McKenna (1995):

The Origins of Modern Management Consulting, pp. 51 ff.

See McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, pp. 16 f.

See Fink (2003): Eine kleine Geschichte der Managementberatung, pp. 4 ff.

Own figure based on Biswas/ Twitchell (2002): Management Consulting: A Complete

Guide to the Industry, p. 19;. Poulfelt/ Greiner/ Bhambri (2010): The Changing Global Consulting Industry, p. 15; Kennedy Consulting Research & Advisory

(2010): Consulting Market Research, website.

Own figure based on Fink (2005): Machiavelli, McKinsey & Co., p. 190.

Through the merger of Watson Wyatt and Towers Perrin in 2010, now part of

Towers Watson.

In the meantime, part of HewittEnnisKnupp, an Aon Company.

In the meantime, renamed as Mercer Investment Consulting.

In the meantime, part of HewittEnnisKnupp, an Aon Company

Own figure based on and according to the criteria resp. methodology of Biswas/

Twitchell (2002): Management Consulting: A Complete Guide to the Industry, p.

15; Pensions & Investments (2010): Research Center, website; Thomson Nelson

(2010): Database, website. For a comprehensive list of the ‘Top 50’ management

consultants comp. http://www.stormscape.com/inspiration/website-lists/consulting-firms/ [accessed November 12, 2010].

Left half marked in dark grey and right half in light grey.

See Myners (2001): Institutional Investment in the United Kingdom: A Review, p. 67.

Originates from Arthur Andersen; in 2002, Arthur Andersen ceased to exist as a

result of the Enron scandal.

The dotted fields show consulting companies with an auditing background.

See Poulfelt/ Greiner/ Bhambri (2010): The Changing Global Consulting Industry, p.

7; McKenna (2006): The World’s Newest Profession, pp. 17 and 235 ff.

See Niedereichholz/ Niedereichholz (2006): Consulting Insight, p. 187.